Stealing and Lying from a Montessori Perspective

Stealing and lying are two deviations from healthy behavior. They are perfectly normal things for children to do, especially as they explore the range of societal behaviors during their elementary years*; expect that all children will spend some time experimenting with each. When they are testing out what will happen, most find out and logically stop doing it. But when a child develops a pattern of stealing or lying, what then?

From a Montessori perspective, repeated stealing and lying are not “normal” behaviors for a child reaching their full potential of character. It’s like testing out something but getting stuck in the “repeat” mode and not being able to snap out of it. Everyone has a conscience, so if the conscience isn’t overriding the temporary benefits from the stealing (Those cookies tasted great!) or lying (I got what I wanted again!), then you need to step in to help.

Dr. Montessori suggested that when the environment supports children’s human tendencies such as those towards work, order, exploration, communication, and manipulation (i.e., touching and movement) and frees up their inner energy for their self-formation, they will “normalize” themselves over time. This means that they become increasingly calm, focused, productive, happy, compassionate, organized, and all other positive qualities. In essence, they will reach their full potential—as unique as each one is—which is their “normalized” self. We see this happen with the children in our Montessori classrooms with their age-appropriate activities in school, and at home with similar satisfying opportunities.

To create an environment that encourages this natural maturing process, we must offer useful activities that help children refocus on positive behaviors. Sometimes, we must remove distractions and temptations for a time. Socially, a child may be feeling uneasy or nervous and may get caught up in social drama, to then find themselves drawn to cause some trouble for others with stealing or lying. Whatever the reason a child chooses this anti-social behavior, they need assistance from the adults and other children to refocus their attention and energies on positive actions.

Practical Suggestions for Helping Children who are Stealing or Lying

If a child is stealing, tell them you need their help, and give them a positive role or job. Employ them in remedying the situation in a non-accusatory manner, perhaps by suggesting they organize the items in question. Point out to them afterwards how their actions helped the group/family or led to a chain of positive events.

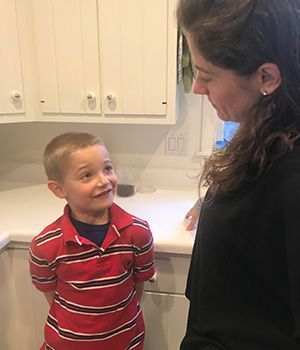

If a child is lying, and you are sure, gently call them on it (“Actually, that isn’t true”) and immediately point to what they can do that’s positive (“Your brother had his trucks in this basket, and we need to get them back in there. Could you help me look for them? Let’s start in the kitchen…”). The proposed activity might be a project, a piece of work, or something that interests your child. If you’re not sure whether they are lying or not, no matter; if you sense that it’s a lie, say, “Hmm, it just feels unsettling to me,” and progress with a project, an interest, or some positive action that your child can partake in.

In both these examples, there is little point in punishing, humiliating, reprimanding, or arguing. By the time they’ve reached age five, children already know much of this material, and it becomes a game for them to master. If you are now seeing an emerging pattern of stealing or lying, you’re best off abandoning any initial urges to punish, threaten, or bribe. At this point, your child knows that they shouldn’t lie, they know it upsets you or others, and they are having a hard time not doing it anyway. Rubbing it in probably won’t lead to the solution.

In the above suggestions, we are going straight to the solution, with no dilly-dallying on the crime. In other words, you are showing the child the path to rebalancing themselves. When we are balanced and feel good, secure, and content, we tend not to steal, cheat, or lie. Human beings have inner urges to do the right things, to be their best selves, to be “pro-social.” Dr. Montessori’s approach employs these instincts and steers us to use this positive psychology in our teaching methods and in our parenting.

When your child has been busy doing more positive things—helping to organize the closet of items they had been stealing, making a doll to give the sister she stole from, helping you buy more cookies at the grocery store, or unpacking the groceries in the kitchen—you might later address the previous, undesirable behavior:

“Jack, you were really helpful just now. You know, earlier today when you ate the cookies, how were you feeling?”

“I don’t know.”

“I bet they tasted pretty good. You really love cookies.”

“Yeah.”

“It’s a problem when you eat them all, though, because they aren’t there for the rest of us. I was sad when I wanted one and found they were all gone.”

“I’m sorry.”

“OK. Apologizing is a helpful response. Thank you. I feel relieved. Let’s think of what you can do next time you really want cookies. Do you have any ideas?”

“Well, I knew if I asked you, you would say no.”

“You’re right, I probably would have. I know you would have felt disappointed. But then we could have talked about that and found a better way for you to get a cookie.”

As such a conversation progresses, you get down to making an agreement for next time, or sharing your feelings about stealing and lying, and along the way, you are having a heart-to-heart without blaming or shaming. You are helping your child—in an emotionally neutral tone—to face their behavior and make a decision to try to do something differently the next time. The goal is simply to open the dialogue, to get them thinking, to help them develop their own conscience, rather than to assert yourself as the “Ruler” who directs their behavior. Our job as parents is to support the development of our child’s own conscience, which is a gradual process.

As I was recently so painfully reminded by a psychologist, “Parents cannot follow their teenagers into every dark alley. The only one that goes in there with them is their conscience. You’d better get used to it.” (Ouch!) So, helping our children build a strong conscience is the goal. And to keep our focus there, we need to point to positive behaviors, not spiral downward into punishments, threats, warnings, and diatribes about how their behavior made us feel. This doesn’t mean we can’t be honest about feeling mad, sad, or disappointed—but our feelings cannot serve as a driving force to change children’s behaviors because when they reach adolescence, that dynamic of trying to control another’s behaviors turns to turbo mode. That is a game where every player is a loser, and the stakes are much higher!

The more your elementary-aged child tries to deny, point fingers, or insist, the stronger their fear and anxiety about right and wrong, and about your reaction. The only way through this forest and out the other side is to diffuse this intensity. As parents, we have got to be less emotional, less forceful, less righteous, less disapproving—a very hard feat for most of us. We feel so responsible for our children’s behaviors; we take it so personally! But when we can get ourselves out of their way, the more direct the child’s relationship to their conscience will be, and the swifter their recovery to normal, healthy behavior.

In The Absorbent Mind Dr. Montessori explained, “Neither severity nor kindness will solve the problem…If the child is placed on a path in which he can organize his conduct and construct his mental life, all will be well…These are not the problems of moral education but of character formation. Lack of character, or defects in character, disappear of themselves, without any need for preaching by grownups or for grown-up examples. One does not need to threaten or cajole, but only to 'normalize' the conditions under which the child lives.”

To "normalize" the environment means to put our attentions on supplying some interesting choices of activity which have real purpose and connection to the home, family, or natural surroundings.

Montessori wrote, “What advice can we give to mothers? Their children need to work at an interesting occupation; they should not be helped unnecessarily, nor interrupted, once they have begun to do something intelligent.” In this way, we include our children in the purposeful work of the home and family, and we support them to concentrate and engage in this work.

Ultimately, it is this balancing of the whole personality which Montessori felt was incredibly important and universal: “We find this phenomenon repeated…with children belonging to different social classes, races and civilizations. It is the most important single result of our whole work. The transition from one state to the other always follows a piece of work done by the hands with real things, work accompanied by mental concentration.”

Montessori emphasized, “The essential thing is for the task to arouse such an interest that it engages the child’s whole personality.” This point is critical: In order for an activity to really engage a child’s whole personality, it must meet the match of challenge for them. It cannot be too hard, but it must be challenging enough to demand the child’s attention. Most of the things you need to do around the house, on a child’s level of difficulty, are good choices for such activity.

Many psychologists recommend a non-emotional response that focuses on “How can we fix this now?” for lying and stealing. Most recommend helping your child to clean up the issue they created. The less pointing, shaming and blaming, the easier it goes. If your child refuses to join you in cleaning something up, returning it, or clearing up a breach of trust, model doing it yourself, and then try to involve your child in some balancing, engaging activity (which is also a great way to head things off at the pass) that absorbs them and gives them a constructive home life environment.

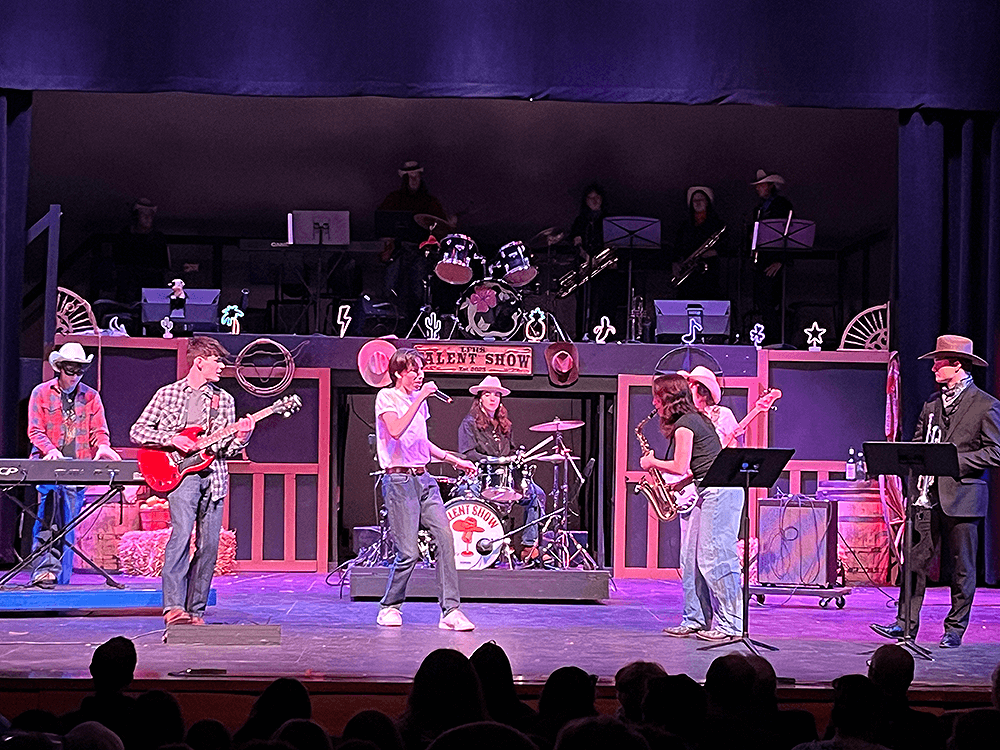

I love Dr. Montessori’s wisdom in pointing us towards meaningful activity as the answer. It resonates with the work of Csikzentmahalyi, who coined the term “flow” for that happiest, most satisfying state. Including your children in purposeful activities is a remedy for many situations, no matter their age—even with adolescents. When our sixteen-year-old gets ornery, wants to argue, or pushes the boundaries, my husband and I find that asking him to cut the tree lights off the outdoor tree, fix a cabinet, solve a problem for us, or make a meal always helps him return to his better self. It seems to bring a person of any age back into the fold, centers them to find their purpose and worth, and places them in society as a good citizen once more.

* Very young children under age five may not even know or understand what they are doing when we accuse them of "stealing" or “lying.” They just know they took something they wanted or tried to make something believable to others by saying it. With very young children, a simple response without too much talking is advised. Let them see you remedy the situation, and they will absorb the rights and wrongs of behavior by observing. The elementary years are really the time when morality becomes a conscious quest, and this is what this article is referring to. For a better understanding of moral development within a Montessori framework, see our blog post How our Children Develop Moral Values.

Recommended Reading

How to Talk so Kids Will Listen and Listen So Kids Will Talk by Adele Faber & Elaine Mazlish

Parenting with Love and Logic by Foster Cline, M.D. & Jim Fay

Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience by Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi