With children under the age of six, in the first plane of development, the Montessori-trained teacher invites each child to his or her presentation of a material. He or she speaks slowly and clearly, emphasizes his or her graceful, deliberate motions to entice children this age to imitate such self-control, and gives opportunity for the child to repeat the exercise many times. The “lesson” is driven by the child’s innate desire to focus and to mimic and internalize organized sequences and exaggerated movements.

A teacher working with children in the second plane of development, by contrast, must appeal to the very different characteristics that drive children ages six through twelve. The elementary-trained Montessori teacher, therefore, speaks and moves more rapidly. He or she asks questions to get the children thinking, wondering, and making connections to previous knowledge. The children’s curiosity drives the “lesson.”

At any age, the teacher invites the children to touch and move the materials as early on in the presentation as necessary and possible. The presentation becomes an interplay of watching, taking turns, and discussing. A presentation, or “lesson,” may be as brief as two minutes or last as long as twenty minutes, depending on the content and the children involved.

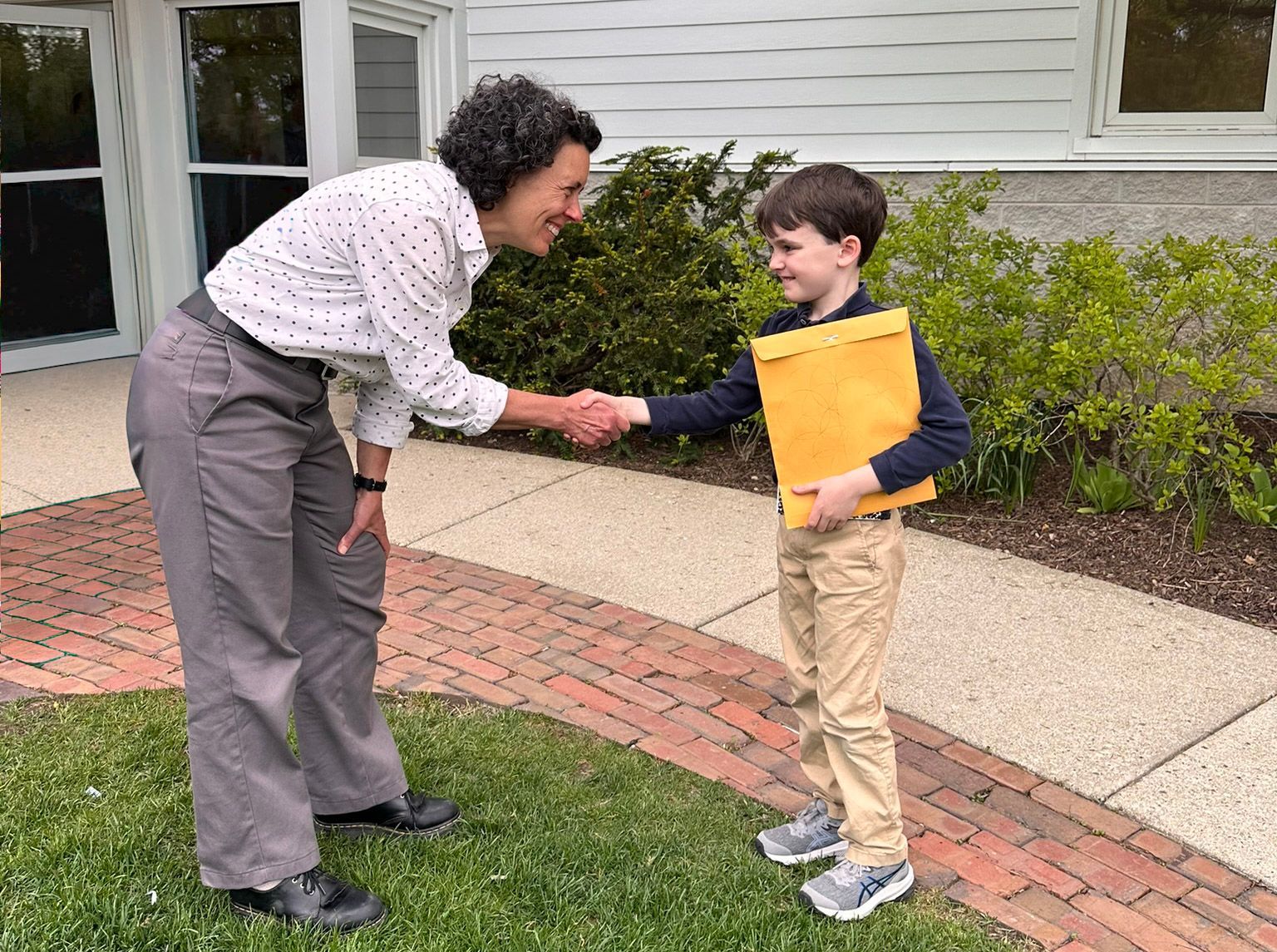

A Primary Presentation

In a Primary classroom, the teacher walks over to three-year-old Dominique, who is coasting along the shelves, looking restless. “Dominique,” she bends down and faces him, “I’d like to show you something new. Would you come with me, please?” Dominique nods and follows her over to a shelf. She again bends down and faces him, touching the edge of a tray on the shelf gently with one hand. “This is the Flower Arranging.” Dominique smiles widely at her and nods. “Here is how we carry it.” She squares herself to the shelf, reaches forward with both hands and carefully wraps her hands around the two outer edges of the tray, slowly lifts it, takes a step back with each foot, and stands up straight, holding the small tray in front of her waist. She looks at Dominique, who looks like he’s about to hop up and down, he is so excited. She replaces the tray carefully, straightens up, and says, “Your turn.” He squares off to the shelf, lifts the tray and holds it level at his waist, turns, and smiles up at her. She smiles, too, and then walks slowly to a floor table and sits down next to it. Dominique follows her, carrying the tray and looking down at it. He carefully sets the tray down on the table.

“We need something else. Come with me.” The teacher walks back over to a large vase of flowers on the shelf close to where the Flower Arranging tray was. She turns to Dominique, standing beside her. “Would you like to pick out a flower?” He points to one and his teacher shows him how to lift it out, holding the others back with her other hand. She invites him to choose another one, until they have three, which Dominique carries back to the table. Next, the teacher shows him how to carry a tiny pitcher from the tray. Dominique picks up the pitcher with two hands, as she has demonstrated, and follows her to the child-level sink in the corner of the room to collect water.

When they return to the table, Dominique’s teacher shows him, step by step, how to cut the flower stems, remove the extra leaves and stem parts, and put these into a small bowl that he can later empty into the garbage. She shows him how to fill the vase with just enough water and how to carry the tiny vase, with the flowers and a cotton doily from the shelf, to a child’s table and place it there.

At the end the teacher asks, “Would you like to make another arrangement?” Dominique nods and she tells him, “OK! You can take out the Flower Arranging whenever you’d like to. I can show you how we put it away when you are finished with it.” She smiles, walks away to work with another child, and Dominique walks to the large vase of flowers to choose three more flowers.

Every presentation is different, but some steps are the same: the teacher invites the child to a presentation, she (or he) shows the child where the material is on the shelf, so that the child can find it again next time and knows where to put it back. The teacher tells the child the name of the exercise and shows him how to carry the tray. She demonstrates how to put it back on the shelf, then invites the child to carry the material to a table, rug, or floor table. She shows the child how to do the exercise. She tells the child he can choose this material any time in the future or gives them any limits about it—such as, “Please come tell me when you’d like to do this”—if applicable. In other words, the teacher orients the child to what they are about to do, presents the steps to the exercise, and suggests it as a future choice for work. It is a very respectful way to interact with children and to teach them new things.

While every teacher, child, and exercise differs, the Primary teacher moves slowly and deliberately, is direct with her (or his) words—gentle and inviting, positive and clear. She appeals to young children’s desires to move, to touch and engage in the activity, and to focus their attention on details. She is calm, but quietly charismatic.

An Elementary Presentation

The Elementary teacher, by contrast, invites children to exercise their newly budding resourcefulness by asking them to bring various things to the lesson as needed, such as a clipboard from the cabinet, paper, pencil, or perhaps a ruler. The Elementary teacher appeals to the children’s social natures of six- to twelve-year-olds. She (or he) begins presentations by asking questions, and gets a discussion going right away.

In a Lower Elementary classroom, a teacher gathers three seven-year-olds for a lesson and invites them to bring a flat purple box of compartments to a table. She asks each to bring another component that will be needed for this lesson: the box of grammar symbols, which they are familiar with from previous lessons, and a purple box of cards that match the purple box of compartments. They sit down to face their teacher, and she begins, “Remember when we worked with the Verb Grammar Box? Well, today we’re going to talk about another part of our speech. I’m going to ask you to do a few things.” With a sly smile, she asks, “Would you please sit underneath the table?” The children giggle, look at each other, and then push out their chairs and move under the table to sit there, laughing. The teacher smiles down at them and nods. “OK, great. Come on back to your chairs.” The children do this. “Now, how did you know where to go?” They discuss this, and the children point out that she said the word “underneath.”

“So this word, ‘underneath,’ told you where to be, in relation to the table.” They concur.

She asks them to do a few more amusing things: “Tommy, would you go stand behind Debbie’s chair, please?” Tommy looks confused but stands and does this. “Ah, I see you’re standing behind Debbie’s chair. How did you know where to go?”

“Well, you said to stand behind her chair.”

The teacher nods, looking down and scratching her head. “I see. Sheryl, would you please put the tissue box on top of the supply cabinet?” Sheryl goes and does this while the other children watch, amused. Sheryl comes back, and the teacher asks, “Now, I’m curious, how did you know what to do?”

“Because you told us!” Tommy says, laughing.

“But what words told you?” They discuss this for a few minutes.

Then, the teacher turns her attention to the purple box of compartments and says, “I am going to show you how you can explore these words further. Let’s begin by setting these cards into the corresponding compartments here, and then we can read the first one together.”

After placing the cards neatly into the compartments of the box, Tommy, Debbie and Sheryl put their heads together and read the first card, sounding the words out loud: Set one chair opposite another chair. They do this action, discussing what “opposite” might mean.

Then their teacher says, “OK, let’s put the grammar symbols over the words, as we have before [in past lessons], for the article, noun, and verb.” They do this, then the teacher holds up a small, green, bridge-like symbol and tells the children, “Here is the symbol for these words that tell us where something is in relation to something else. We call these words or phrases the preposition.” The teacher places the small symbol above the card with the word “opposite”.

The three children read and act out the next card while their teacher watches them. This one reads: Arrange two chairs along the wall. Arrange two chairs against the wall. The children sift through the many one-word cards in the compartments of the box, searching for the ones that make up these two sentences. The cards from each part of speech have their own color-coded compartment. The children place the corresponding symbols above each word in the sentences they have constructed, then add the new symbol they just learned above “along” and “against”.

The teacher leaves the children to continue. They delight in reading and acting out each command, sometimes laughing, and generally having a great time. They rush back to the table to symbolize each sentence and to pull out the next card. This goes on for about half an hour.

Notice that Elementary Montessori teachers ask many questions. In other lessons of physics, chemistry, math, or geography, they might ask, “Why do you think it’s like that?” “What might that tell us?” “If we choose this amount, then what might happen?” Such questioning is not done to trick the children or to test them (although it does give the teacher much information about the child’s comprehension and self-expression), but as an invitation to figure it out together. It is done in a friendly, inquisitive manner. Every time a teacher gives a presentation, the child is oriented to another work choice in the room that is now available to him or her. In this way, the teacher exposes each child to their choices for work, expanding it over time, covering all subject areas during their three years in the classroom.

What Happens Next?

“Follow-up work” happens when a child chooses the material again without the teacher and works with it by himself or herself. (In the case of Elementary children, the child may also do follow-up work with a group of peers). A child might simply work through the exercise and replace it to the shelf, or she might produce pages of writing and illustrations. An Elementary aged child might produce a research report, or any number of artistic, language, or mathematical extensions of their work, when appropriate. He or she might conduct a scientific experiment, collect specimens, or make other numerous expressions of their expanding knowledge. In this way, the Elementary child’s growing body of knowledge may be represented by an original portfolio. The Elementary teacher will suggest ideas for follow-up work and will guide children to improve the quality of their work as they progress.

The Teacher’s Job & The Materials’ Job

The Montessori teacher’s job is to keep track of what he or she has shown each child, noting the child’s comprehension and progression. The teacher plans and makes adjustments where help is needed. While it may seem as though Montessori teachers do very little when they’re leaving children to do the work on their own, the Montessori teacher has the task of observing carefully and stepping in to guide children back to productive activity, if necessary. By giving these short and frequent presentations to many children, the Montessori teacher is always interacting and modeling industrious activity—all day long! With this teaching format, the Montessori teacher can cover the wide range of subjects necessary, with the varying abilities, learning styles, and interests that children have. She or he is able to meet individual needs in a classroom community in a natural and seamless manner.

The Montessori materials are not to be used as didactic materials for the teacher to teach with, but rather as learning materials for the children to learn by using. Dr. Montessori explained, “The work of education is divided between the teacher and the environment…The profound difference that exists between our method and the so-called objective lessons of the older systems [such as with Froebel’s teaching materials] is that the objects are not a help to the teacher. The objects are, instead, a help to the child himself…It is the child who uses the objects, it is the child who is active...”[1]

In the examples above, you can see how the teachers invite children to take part in the presentations and to touch the materials, or perform actions, right away. The children then continue with the materials long after the teacher has stepped away. The real learning occurs while the children work with the materials, after the teacher has left them. This is why it is so important that children spend time working independently from their teacher.

This makes clear that the teacher must know precisely how to present the use of each material so that the children can use it in a way that is truly useful. A Montessori teacher presents the materials in a definite sequence, progressing in difficulty, with each step building on the prior ones. Children make discoveries with the materials only when they are interested in that material and their minds are ready to comprehend, two conditions that a trained teacher learns to recognize and respond to. If a child works with a material repeatedly during a time of readiness, he or she may see something revealed in the materials; he or she discovers a truth independently. In this way, the teacher has an important guiding role, but she or he is not the center of the child’s learning experience—only the one who points the way.

Teachers give as many presentations on how to use the materials as possible, every day, to as many children as they see are ready for new presentations, or in some cases, re-presentations. There is a balance between presenting to or helping a student and leaving them alone to concentrate on their work and develop a deeper focus. Although the presentations themselves and how to determine when a child needs a certain presentation is taught in the teacher training courses, Montessori teachers must develop for themselves a sensitivity and awareness of what to look for when observing the children and making these determinations. Having many children in the room with only one teaching adult protects the children from having an adult interfere too much; it means that the children must develop some independence in their learning, and that they figure out how to learn by watching other children working. The children also help one another, so that their own skills and knowledge deepen through peer-to-peer teaching. In these ways, the children develop resourcefulness through their work.

Paula Lillard, for instance, recalls many instances of sitting down to show a child something for the first time, only to find that he or she understood the material so readily that a presentation was hardly necessary. In such situations, a child had watched other children working with the material and had been intrigued with it. Dr. Montessori called this “indirect preparation,” which eases the difficulty of learning. In this case, a child may have also observed Mrs. Lillard presenting a material to others and retained much of what he or she had witnessed. Delighted that the material was now in their possession, a child in this case might want to repeat what they’d seen others do, or might be ready for their teacher to go straight to a subsequent presentation with the material, which the teacher is free to do.

The Magic!

Having the flexibility to respond to each child means that the Montessori teacher can guide every individual to a material and its use most effectively. The timing, manner, and language that a teacher uses will be customized for the child or children he or she is working with. Like a guide who points the way, the teacher allows the children to teach themselves, through the materials. Graduates often say that in Montessori, they learned “How to teach myself.” This ability to learn by their own process was fostered in this intentional way and endures in their spirits, always.

[1] p. 149, The Discovery of the Child