Parents across the country were given a new job this month, with no warning and no training. Because of nationwide school closings, home school is now a reality for families. This has been jarring, upsetting, confusing, and overwhelming for many households. Parents with no plans to enter the educational field now feel responsible for their children’s school experience. Even I, a Montessori trained teacher with three years of experience in the classroom, never had this job in mind. In fact, two months ago, I said, verbatim, “The only way my children would ever be homeschooled is if someone else homeschooled them.”

Obviously, the universe had other plans.

What I have to my advantage right now are my Montessori trainings and my classroom experience. But what may be unexpected for most people is that I am not using this experience to help me teach my children. I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again, I am not worried about their academics. If they want to do a research paper on black holes, then that is their business, but if they want to do puzzles, write stories, bake, and read, then I am happy with that.

What my Montessori teaching experience has given me is a way to conduct myself and manage my children during our “home school” mornings. (I put the home school in quotations, because my seven-year-old recently referred to it as “fake school,” and I couldn’t find a reason to argue with her). For most of my children’s lives, I’ve worn a “Mom” hat. But, in order for our mornings to go (somewhat) smoothly, I’ve need to put on my “Montessori teacher” hat. And while, on the one hand, I am always myself with them, this hat reminds me of some practices I can engage in order to help our mornings feel productive and peaceful for all.

So, what happens when I wear a Montessori teacher hat? What behaviors and expectations do I utilize?

Montessori Teacher Practices

Prepare the Environment

One of the first things we learn to do in the Montessori training is to prepare our children’s environment. At school, this means organizing the materials on low shelves; having paper, pencils, and other supplies available where children can reach them; and generally creating a room where the children can function independently without a lot of extra support from their teachers. At home, this looks a little different, but many of the principles remain the same.

Look around your home and do your best to make it a place where your children can work independently. Put their work, toys, supplies, and snacks within their reach. Put up the materials and food that you do not want them getting into. Make sure they know where everything they need is. Reduce the activities available to an appropriate number for your child so that they aren’t overwhelmed, and so that they can clean up mostly on their own. Every home environment will look different according to your own family and needs, but your goal is to promote independence and positive choices by reducing obstacles and distracting activities. (See an earlier blog post about helping children develop concentration at home)

Observe

Another basic tenet of the Montessori training is observation. Observation is an integral part of the Montessori method. Maria Montessori herself was a trained medical doctor, and used the scientific approach in all of her work. To truly observe is to watch what your children are doing without emotion or biases.

When you can utilize this skill in observation, you can come to a better understanding of why something is happening, what your child might need, or what needs to happen next. In our Montessori training, we are taught that the first thing we need to do when we encounter a problem in the classroom is to observe. This means that we take notes, physically or mentally, and we watch how it unfolds. What seems to precede it? Is this child truly frustrated or are they just struggling and are about to figure this out? Does this tend to happen at a certain time of day? Does this tend to happen in a certain area in their environment?

Earlier today, a parent asked me about a home school activity--she wanted to know if it was appropriate for the morning’s work. My first response to her was: Observe. How do they act while they are doing it? Do they clean it up on their own after? How do they act afterwards? Are they calm and content? Can they make their own choices about what to do next?

We can answer so many answers on our own, if we give our mind the time and space to see our children for who they really are and what is really going on for them at any given moment. By using observation, our children themselves can tell us what is working and what we might try next.

Connect, Not Teach

Even in the Montessori environment, teachers do not think of themselves as “teaching” concepts. We connect the children to the materials, and the children teach themselves through the materials. There is a famous story in Montessori where someone asked a six-year-old, “Who taught you to read?” She answered, “I taught myself, of course!”

The world teaches our children much better than we can. Our children teach themselves much better than we can. It is not our job as parents to teach our children, even at home school. Human beings are born with amazing intrinsic motivation for work and acquisition for knowledge. How else would we have created civilization, if not with an inborn desire for this? I do not need to convince or force them to learn. I just need to find a way to light their inner flame.

Given this trust I have in their own inner drives, I look for ways to connect my children to activities, rather than teaching or forcing. For my five-year-old, it has helped when I have done an activity in front of her. “Do you want to watch me write a story?” I asked her. Then I wrote a simple story very slowly in front of her: “The dog went out. He barked at a man. I picked him up.” I read it out loud to myself, smiled in a satisfied way, and drew a simple picture to go with the story. Before I even stood up, she was hustling to the paper cabinet to make her own story.

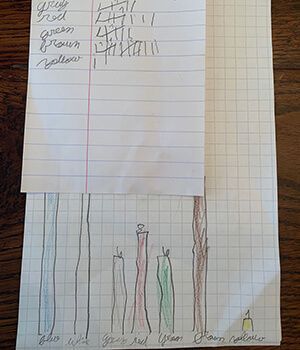

I take a similar approach for my seven-year-old. I do not want to be heavy-handed, or I will take over the ownership of her education. “I wonder how many houses on our block are blue,” I said to her. “I wonder how many are white. I wonder what the most popular color is. Do you know what a survey is?” I asked her. In this case, she did know, and she eagerly set off for an independent walk around the block, where she recorded house colors and took note of how many of each color she spotted.

We marveled at her results and then I said, “It is sort of hard to see what the most popular colors are. Do you know what a bar graph is?” I started to show her, and she hastily took over the paper. “I’ve seen people in my class doing that,” she said. And she completed it on her own.

Sometimes my musings and examples do not go as well. Sometimes my children want to grumble and do nothing. But if they are going to get excited about work on their own, it is always because I found a subtle way to inspire them by means of curiosity or example. It never comes from my demands or instruction. Connecting them to their world remains our best avenue for productive activity.

Speak With Authority

This is as simple as “say it like you mean it,” but it is surprisingly hard. It took me most of my first year as a teacher to learn how to speak directly and firmly to the children. By my nature, I prefer to be in conversation with people. I prefer reading how they are interpreting what I am saying, checking in on how they feel, and seeking approval. All of this is adaptive and positive for my relationships with adults, but with children it weakened their confidence in me. Every time I made a statement in the form of a question, or said “Okay?” at the end of a request, I eroded my authority.

While it is true that we are equals in dignity and humanity, it also is true that I am older and wiser. And while I want to show my children respect and kindness, I also want them to feel secure knowing that I am the adult so that they can be the children. They have confidence when I have confidence. I can say to them, “No, we aren’t going outside right now.” And then, “I don’t have time to talk about the reason now, but I can tell you later if you ask me.” They may resist and grumble, but ultimately, and through my consistency, they learn that they can trust me to make good decisions for our family.

I do not, of course, always talk like this to my children. We are often in conversation, making suggestions, asking questions, and making decisions. But I have this voice to fall back on when I need to make my point. My grandmother Paula Polk Lillard calls this “the unapologetic no.” It’s the way you say “No” when you know that you are in charge, and you are capable of making the best possible decisions for everyone involved. When you believe, they can believe too.

Freedom and Responsibility

Many people think of Montessori as, “That school where children can do whatever they want.” This is both true and not true. Children have the freedom to make positive and productive choices of work. They have the freedom to have time to reflect. They do not, however, have the freedom to be destructive, distracting, or disruptive. And they do not have the freedom to avoid work for extended periods of time. A child’s freedom expands and contracts along with their capacity for responsibility on a given day.

I use the same principles in our home. When my children are capable of responsibility and self-regulation, they have more freedom, as well as the privileges that go along with that freedom. They may make their own work choices in the morning, they may go on a walk around the block without me, they may listen to audiobooks in the afternoon, and they may explore baking in the kitchen.

When I see that they are having trouble directing themselves and being responsible, their freedom shrinks, and, in those moments, I lend them my discipline. I invite them to do their work next to me. I give them two choices of activities, in the hopes that making one limited choice and then having the positive experience of that work will help to regulate them. As I see their responsibility growing, their freedom increases. And, if today is a day when they need to borrow my discipline, then I will keep them close to me, and limit their choices for the time being. Tomorrow is another day!

Final Thoughts

None of this is magic. None of this is easy. None of this works every time. And there are some days when it feels like nothing works. There are some days when I have to excuse myself to the bathroom and cry. There are some days where I don’t make it to the bathroom before I start crying, and all we do is run around outside and listen to audiobooks and try to be kind to each other even though it is hard.

None of us were prepared for this. Parents, teachers, children, doctors, nurses, and the hundreds of other jobs that have changed suddenly with these extraordinary times. But human beings are extraordinary, too. We are going to learn things about ourselves, our neighbors, and our families that we never imagined. We will wear many hats during this time, and even while we struggle with the worst in ourselves, we will also find the best. This is a time for patience, kindness, and letting our hearts open to the possibilities inside of ourselves and the world.