Articles

Montessori vs. The Conventional Model Anyone who has seen a Montessori school understands that it is fundamentally, startlingly different from a conventional education. While students complete their experience at a Montessori school with similar academic abilities as their counterparts in conventional schools, they go about these acquisitions in a completely different way. A Montessori education is, at its core, a child-centered education. This does not mean that children do whatever they want while they are at school. It means that the approach assumes that the child is an active agent in their educational experience, and that they will construct themselves, given the right structure, guidance, and materials in their environment. The formal schooling that is familiar to American culture today originated hundreds of years ago in monasteries. It further solidified its methodology in the late 1800s and early 1900s when industrialization was introduced to the United States, and schools began to depend upon the “factory model” to produce good workers en masse. Since then, study after study in the field of child development has confirmed that this is not the ideal way for children to learn. Yet, when universities, schools, and lawmakers propose improvements to the educational system, they simply add on to a system that is already not working well, by (for example) increasing testing, making rewards even more compelling, and dividing children into even more pronounced groups by ability and age. Where Do We Go From Here? In Dr. Angeline Lillard’s new article, Why the time is ripe for an education revolution , which was published in Frontiers in Developmental Psychology, she argues that this is a cultural moment when the educational system ready for a paradigm shift - one that would move away from a fundamentally teacher-text-centered (TTC) base and towards child-environment-interplay (CEI), which recognizes that “A child develops into an adult by constructing an elaborate representation of self and world, and learning to interact with and exercise agency in that world. This development occurs in a dynamical, non-linear fashion across childhood” (Lillard, 2). The CEI model is supported by modern research and is an ideal fit with Montessori. Lillard supports her argument by comparing today’s cultural climate to the factors at play in the 1500s when astronomers moved away from an earth-centered view of the universe to a helio-centered view of the universe. While there were recognized flaws in the previous understanding of the universe, it wasn’t until certain cultural elements were present in the 1500s that civilization as a whole was ready to transition to the realization that the sun was at the center of the universe. Just as in education, simply knowing that something isn’t working often isn’t enough. Human nature is compelled to continue to make adjustments and explanations for what already exists rather than leaping to a brand new perspective. As it was 500 years ago, Lillard believes that the world is ready to make the leap to a new approach to schools. The time is ripe for an education revolution. And Montessori is ready for it.

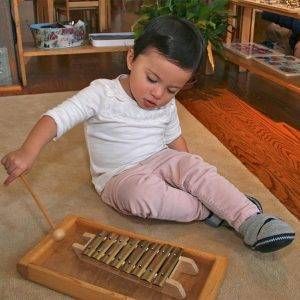

In a previous blog post, A Montessori Guide to Technology and Teens , we explored how we can help our adolescents begin to use technology responsibly, as part of adapting to the adult world. Here we will discuss a Montessori perspective on the role of technology and screen time for younger children, under age twelve. What’s the Big Deal? These days, messages from marketers are strongly pro-technology for children, and even some educators are strongly pro-technology. Everyone has their own experiences to base their judgments on; if you’ve seen negative results in your own family, you might look to the current research to validate your sense that technology is not a good fit for childhood. Conversely, if you’ve had positive or neutral experiences with your children using technology, then you probably think people are going bananas over something minor. Either way, most parents don’t have the time to conduct a thorough Ph.D.-level investigation before deciding whether their child can have that video game or the latest digital device they just opened under their grandparent’s Christmas tree this year. So, what are we to think about this debate over technology for children, and what do we want to steer our children towards in our own homes? When we look at this issue from the perspective of a Montessori approach, we consider: what children need for optimal development, the importance for a child of building their foundation for life, preparing your home environment, basing your decisions on observations, and keeping your long-term goals in mind. What Children Need for Optimal Development Dr. Montessori pointed out that under the age of six, children need reality so that they can form their understanding of it. They need to touch, feel, taste, smell, move and experience the real world. Human beings are sensorial learners when young. From their sensorial explorations, young children learn things about physics, textures, and qualities of the world. Consider that no screen can provide this information in a natural or full-sensory way. Children need to discover for themselves what kind of structures collapse under pressure and which ones don’t, and to figure out why by exploring and experimenting. To be effective, this has to happen in reality, not virtually.

Learning Emotional Balance Through Montessori: How We Steel Our Children Against the “Superkid” Perils When I read the New York Times Article in July, 2015 by Frank Bruni, “ Today’s Exhausted Superkids ,” and “ The Silicon Valley Suicides: Why Are So Many Kids Killing Themselves in Palo Alto? ” by Hanna Rosin in The Atlantic in December, 2015, I was deeply saddened that more parents don’t know about the benefits of taking a Montessori approach to learning emotional balance at school and at home. You may have read these or other articles about teens struggling to balance themselves when pushed to excel. Too many have tried to escape what feels like suffocating pressure from their parents and high-achieving communities with drugs and even suicide. Although the issues in each case are complicated, such articles remind us to keep what is most important in the forefront of our minds as parents. At Forest Bluff School, we continually find wise guidance in the Montessori approach to learning emotional balance, which emphasizes healthy self-governance in action as well as thought . What I see in the described stories are problems that stem from adults—perhaps unconsciously—trying to run young people’s lives for them. In contrast, our students at Forest Bluff learn from an early age that they are in charge of themselves. While making numerous choices throughout the day and deciding what work they are going to do next, our children learn to take their feelings and energy level into account. For instance, when a student has been working hard on editing his research paper for an hour with his teacher and practicing presenting it for another hour with classmates, he will usually choose to spend some time drawing the cover while in easy conversation with a friend or by himself in a reflective manner near a window. Because the teacher does not interfere with such decisions, healthy personal habits develop.

Young children in their first explorations of the world about them with their eyes, then their hands and brains working together and finally their whole bodies in coordinated movement, are overwhelmed when they are living in, what is for them, an environment of confusion and disorder. Sometimes such a situation is unavoidable and human beings throughout our history have shown resilience in the worst of circumstances. However, in our affluent societies throughout history we have created environments of confusion and disorder for young children unwittingly by too much stimulation and overabundance of sight and sound. The Internet world is replete with enticing “educational” toys and technological devices marketed as giving one child an advantage over another. In truth, Montessori principles of “less is more” and “beauty lies in simplicity” are better guides for establishing the home that will best serve the inner lives of our children. We don’t want overabundance for our children in our homes (or schools) but it is important that what we do give to them represents the best of our culture and human history – in other words, the best of the human spirit of others. Montessori, for example, in her first International Course in Rome in 1913 when participants in the age of steamship and railroad travel came from as far away as Japan, Australia, the Argentine Republic, India, Turkey, Russia, the United Kingdom, Canada and the United States, to name a few, arranged that they would spend the entire first week of the course, not learning about her revolutionary observations of children but discovering the heritage of Rome, guided by the leading experts of the day in every field from archeology to music to art and architecture. Montessori herself was very much a Renaissance person and she recognized that giving the best of our heritage to our children was necessary for them to develop gratitude and appreciation of human beings of the past and their contributions to human progress and civilization. In our homes today it is important to surround our children with the classics of our culture, the music and art and literature that have stood the test of time. We can have audio recordings of Bach and Mozart, prints of Rembrandt and Renoir paintings, the plays of Shakespeare and children’s classics for reading to our children – just a sample of each at a time so as to create awareness without saturation. At the youngest ages there is an unconscious absorption for the children but in the elementary years this early exposure at home plants “seeds of interest” and provides a foundation for later visits to the symphony hall, art museum or theater for live performances of plays and classical ballet. And, those of us of a mixed background might want to discover more about our heritage, and could go now to start beginning that journey, possibly opening up a whole new culture and wealth of experiences for our children. Having said all of this, I want to caution us as Montessori parents. Beware of grandiose thoughts and plans for children! Those of us in the United States today live in the most affluent country and time in human history. There is danger in our expectations of our selves, of our children, of our spouses, friends and colleagues. As much as at any time in human history, it is essential that we accept our selves and others as the flawed human beings that we are. This is what we are meant to be, not some social media image, dressed up for Facebook, falsely portrayed to the world for its approval. We are spiritual beings on a journey, in Montessori’s words, of the “development of our inner lives.” It is out of this journey, where abstract thought, ideas and imagination originate, that all creative endeavor and human progress come. If we, as parents, concentrate on the “development of our inner lives,” we will naturally set the stage for our children’s path to independence from their birth to maturity at 24 years. If we do this, we can be certain that when our children’s time of trial in adulthood comes – as it eventually does to all of us – they will make it through. I want to close with quotes from a final paragraph in one of John Snyder’s chapters in Tending the Light : “Our job is to help children build a ladder that they can climb from infancy to adolescence; once there, their maturation to adulthood requires that they throw away the ladder we so carefully constructed together. Nothing is permanent about the elementary child, so we guides must fall in love with change. Maybe we shouldn’t speak of throwing away ladders. Maybe we should say , Give a child a ladder and they will climb to the next grade. Teach the child to build their own ladders, and they will climb to the stars. ”

How then can parents help their children under the age of three to build the foundation for eventual independence? A parent’s first response is often to try and recreate the Young Children’s Community (for 18 month to 3 year olds) in the home. However, any parent attempting to do so soon finds that this task is neither possible nor necessary. Instead, we ask parents to bring their child to Forest Bluff at 18 months where we have created an environment that is meeting just the needs of these little ones. We do indeed suggest some ways for supporting your child’s independence at home. It is key, however, that you not interpret such suggestions as instructions. As parents, we tend to hear them in this way because we are conscientious about our children and also because of our own educational backgrounds where teachers consistently told us what to do, and when. Perhaps – with our first children especially – we will have the opportunity in their early years to let them scrub a potato for dinner and put their own clothes in a hamper, but real independence is not going to come primarily from specific activities. It is going to come from a place that you may not have considered before. It is going to come from your child’s experience of you: of your relationship together. We have to begin with who we are, our spiritual selves. The child before us is a spiritual being; we have to address and relate to him or her with the human spirit within us. Motherhood with its forced slow down in activities during pregnancy, nursing and the body’s recovery period, presents the perfect opportunity to reflect on our inner selves and our journey through life to date, our hopes and dreams for the future, our values and those achievements in life that will have the most meaning for us when our life’s journey is complete. Such gains in our inner lives are hard work but they will be with us for the lifetime of our parenting and reap benefits for all whom we touch in every area of our lives. Relating to our children with our whole selves requires time: time to just be with them (no phone in sight or earshot) for a slow paced walk, sitting in the leaves, looking at clouds, reading a book, being a calm presence and enjoying life with them: above all, taking the time to just observe our children, not in a passive way but in an active one. If we make an effort to observe and think through each situation in family life and what might make this time of day go more smoothly, we will be rewarded with a more joyful and peaceful day, both for ourselves and our children. Perhaps dinner could be prepared after lunch, before a quiet time with all the family in their rooms for a rest. Next, everyone could go outside to play and be refreshed just by being in nature, the human being’s original and most natural environment. Even on the coldest days, children and mothers can bundle up and get out in the fresh air, even if only for a short time. In the fall when the time change brings darkness an hour earlier, it might make sense to come in from outdoors and start the children’s baths at 4:00 or 4:30. Children would then be in their pajamas before dinner at 5:00 or 5:30. They could be in their beds for their individual story time with you just afterwards, thereby eliminating any opportunity to get overstimulated and overtired before going to sleep. As you consider ways of arranging your daily schedule to meet the needs of your children in this modern world, I want to mention a major obstacle for all of us. It has to do with being fully present for each other – especially our children. We know that screens, cell phones, computers and much modern technology distract us from face to face contact with each other. We may not be aware, however, that new studies are suggesting that these technological devices can even make it difficult to be comfortable and relaxed after we are no longer using them. Thus they interfere with our enjoyment and opportunity for reflective thinking when we do set aside uninterrupted time for calm and solitude. (See: Reclaiming Conversation by Sherry Turkle, PhD). Finally, we can deepen intimate and warm relationships with our children by planning an environment in our homes that fosters the intellectual lives of our children and of ourselves. Montessori teacher and author, John Snyder in his book, Tending the Light , describes the Montessori environment at home (as at school) as “free, peaceful, rich intellectually.” Montessori gave the details of this Prepared Environment at school for children from early childhood through age twelve. Therefore, Montessori schools throughout the globe are familiar to any child transferring from one to another. Obviously, she could not give details for our varied and unique home environments. However, the principles behind establishing a home environment that is “free, peaceful, rich intellectually” are similar.