Secondary Level/Adolescence

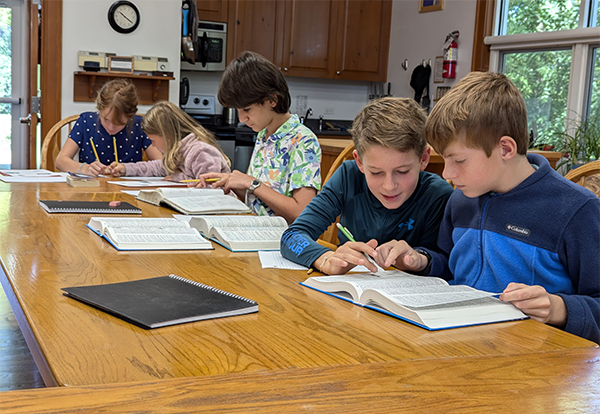

At Forest Bluff School, the Secondary Level is a two-year program for adolescents, in which they continue their self-formation through more rigorous academic study as well experiential learning that includes service and wilderness trips. The Secondary Level has all the hallmarks of a Montessori adolescent program, with a focus on independence, responsibility, self-directed learning, community and collaboration, and practical life skills.

This is the final installment of our spring blog series, Montessori and Executive Functioning. In Part I , we learned how a Montessori education helped Forest Bluff alumni to develop skills such as sustained attention, task initiation, organization, time management, and planning/prioritization . In Part II , alumni share how their schooling contributed to the development of their response inhibition, working memory, emotional control, flexibility, and goal-directed persistence . In Part III, the role of metacognition is discussed. Metacognition: the ability to consider and evaluate one’s own thinking processes Over the course of the creation of this piece, I had the opportunity to speak to many Montessori alumni. I was struck by how, after seeing the list of traits, each one could so easily speak about their executive functioning skills. Every single one was able to choose a topic to discuss. And despite being in the middle of exams, or homework, or their own full lives, they were able to share organized and concise thoughts about their thinking processes, whether it was task initiation, goal-directed persistence, sustained attention, or any of the executive functioning skills. In this way, every alumni I interviewed displayed fluency with metacognition. They considered their thinking processes, and developed articulate and thoughtful analyses of their cognitive abilities. Not only were they able to consider these processes in the present, but they also were able to reflect on their childhood experiences, and relate their current thinking patterns to their Montessori education. Perhaps this is the invitation for me to reveal that I, too, am a Montessori alumni. I deeply appreciate the importance of metacognition. Without an understanding of our thinking processes, we cannot properly evaluate where we need more support, or how to individually structure projects so that we have the best chance of success given our strengths and weaknesses. As I observed during my interview with the young woman about sustained attention, executive functioning traits do not simply exist fully formed in every person. Instead, we need to understand which tools to use when in order to fully utilize our skills. Metacognition makes this possible. Montessori uniquely provides an environment for developing metacognition. From a very young age, students are making choices and living with the consequences of those choices, giving themselves opportunities to assess their decisions and their approaches to their work. When they are very little, this process is implicit. But after the age of six, they record their work in a work journal—their entries becoming more elaborate and specific as they mature—and then they have a weekly meeting with their teacher where they consider their work progress, and make plans for what they’d like to accomplish in the coming week. This cycle of freedom and reflection gives students the space to experiment with their work habits, and then assess how it went under the guidance of a trained teacher. They are not simply told what they did right or wrong. They are part of a regular conversation that considers their individual strengths and weaknesses, and then they are given the liberty to begin their next week with new ideas of how to accomplish the work they’d like to accomplish. This lays the foundation for metacognition. Final Thoughts As I read through the conversations I had with each of these students and parents, I see three important themes. Freedom and Responsibility First, the balance of freedom and accountability (or responsibility, as the Montessori language often uses) is a foundational element for almost every single skill related to executive functioning. Perhaps obviously, in order to develop the ability to make good choices and plans, a person needs a lot of practice making good choices and plans, preferably starting in their childhood. They need to choose what to work on and how to work on it, and also have the space to make mistakes and learn from their choices. Then they need the freedom to choose it again, and to do it differently next time. No matter how many choices a conventional school introduces to the day, it is virtually impossible for them to replicate the intricate and widespread presence of freedom and accountability in the Montessori curriculum. This is partially because it is not enough to simply give the children freedom. They also need specific, regular, and natural opportunities to get feedback on their decisions, whether they learn from the materials, their peers, or conversations with their teacher. They have to have the freedom to make choices, and the necessary structure to learn from those choices. This is how executive functioning skills flourish. A Cohesive and Comprehensive Curriculum Second, Dr. Montessori’s cohesive curriculum supports executive functioning through an entire childhood—from the time the tiny toddler enters the Young Children’s Community until the long-limbed adolescent plans for a semester-long independent study project and prepares a meal for their entire class without a teacher’s help. It does this by gradually expanding the size of the projects while giving children organic checkpoints to assess their decisions and projects. One mother who I spoke to observed the ways this takes place throughout the years: It goes all the way back to the YCC and the Primary because the children are choosing their own work then, too. They may get out a lengthy activity like table washing right before the end of the day. They set it up and then see their classmates cleaning up their work. They experience the trial and error of what fits into the time they have at their disposal. In the Primary, they choose their activities and fill their time. In the Elementary, they record the time it takes to do work and reflect on it. Then in the Secondary Level, they make plans for the future. The children do so many long term projects in Montessori. They not only experience what they did during a certain day, but they also have to manage how to get through a long project. Are they keeping up with their friends who are working on the same project? Are they staying on track for the goals they set for themselves? There’s a constant juxtaposition between the large scale work period and the smaller scale work periods. These larger scale work periods and smaller scale work periods are an essential element of the Montessori curriculum. Learning to navigate this balance over the years creates an important foundation for executive functioning. Celebrating Individuality Finally, and perhaps most significantly, is the respect that Montessori has for the extraordinary individuality of every human being. It not only acknowledges it and supports it, but it also recognizes that our world needs human beings with profoundly different strengths. These executive functioning skills do not all exist fully formed in 8th grade Montessori graduates. The seeds have been planted, so to speak, but it will take time for them all to flourish. Montessori does not produce or polish or make anything in graduates. The academic and holistic curriculum gives children the gifts of deeply rooted awareness, confidence, and experience as autonomous beings with goals. But, given that every person is an individual with unique strengths and challenges, they all will come to the impressive executive functioning that Montessori promises in their own time. Similarly, each skill will show up uniquely in each person. One graduate will exhibit “sustained attention” in a different way from another graduate. In my interview, our sophomore college student sustains her attention through organization and motivation. Someone else might use other habits to arrive at the same place. The beauty of Montessori is that it provides just enough structure for a person to keep building their own scaffolding as they grow into the world and develop their own habits and goals. The alumni mother who I spoke to shared her thoughts on this: “It is unusual for a system of education to simultaneously indulge personality discrepancies and also correct for weaknesses. Montessori doesn’t extinguish divergences in students. It allows us to hold on to the best parts of what made us all different while also holding us accountable for the ways we needed to be productive and accomplished.” Truly, the goal of a Montessori education is not to produce graduate after graduate who all exhibit the same executive functioning skills in the same way. It is to elevate natural strengths and help provide structure and support for challenges. It is to maintain the individuality of each student, and preserve their confidence and love of learning, while also allowing them to develop the tools necessary to thrive in the world. The goal of a Montessori education is to sustain a reverence for the dignity of every human being, and provide a path for each of them to offer their own essential gifts to the unfolding of the universe. References Guare, R., Dawson, P., & Guare, C. (2013). Smart but Scattered Teens. The Guilford Press. Moffitt, T., Arseneault, L., Belsky, D., Dickson, N., Hancox, R., Harrington, H., Houts, R., Poulton, R., Roberts, B., Ross, S., Sears, M., Thomson, W., & Caspi, A. (2011). A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(7), 2693-2698. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1010076108 Randolph, J., Bryson, A., Menon, L., Henderson, D., Manuel, A., Michaels, S., Rosenstein, D., McPherson, W., O'Grady, R., & Lillard, A. (2023). Montessori education's impact on academic and nonacademic outcomes: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 19(3). https://doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1330

This is the second article in our spring blog series, Montessori and Executive Functioning. As parents and educators have come to understand how important executive functioning is for a successful adult life, it has become the focus of many conversations and goals for educational practices. As more research is conducted on the relationship between executive functioning and educational practices, it has become clear that Montessori uniquely supports the development of these important life skills. In Part I , we learned how a Montessori education helped Forest Bluff alumni to develop skills such as sustained attention, task initiation, organization, time management, and planning/prioritization . In Part II, alumni share how their schooling contributed to the development of their response inhibition, working memory, emotional control, flexibility, and goal-directed persistence . Montessori Alumni Reflect on their Executive Functioning Response inhibition: the capacity to think before you act I spoke with a college senior about his relationship with response inhibition. “Being able to think before I act is more important now than ever,” he told me. “The stakes are high in college. Our work is more complicated. There is so much to accomplish, and so much involved in accomplishing it. Additionally, with the many freedoms of college, there are also many temptations and distractions. I have to make careful choices.” Response inhibition prevents us from living in a perpetual state of reacting. It allows us to consider consequences and proceed wisely. He then reflected on how his Montessori education supported this development. “My experience with the science experiment cards in my upper elementary classroom helped me with this skill considerably. Each card would have a sequence of steps which demonstrated a simple science experiment. Failing to effectively do a step would confound the following ones. This impressed on me the importance of being discerning and making sure I was following the steps correctly.” Students have a great deal of independence with these cards. They choose the experiment, gather the materials, perform the steps, and record the results. They are responsible for their work and the choices they make as they perform the steps, without much teacher involvement or oversight. Our senior had more to say about his particular experience in Montessori: “Oftentimes, children learn response inhibition through positive or negative social experiences, which teach them things like manners. However, having the space to fail when working on something tangible provided a space for me to learn a different and important non-social aspect of response inhibition.” There is an important balance of freedom and structure in the science experiment cards—the same balance that is apparent in all of the work choices available in the classroom. This gives children the space to fail, but also provides clear accountability, allowing them to recognize when they have erred. They develop response inhibition as they experience the consequences of their own decisions, and have the chance to make better choices in the next iteration. Working Memory: the ability to hold information in your head while performing tasks A college sophomore chose to talk to me about working memory: “At this point in my life, working memory has become crucial to my learning experience and ability. It is a skill that I’ve [really focused on] since going to college.” Working memory is what allows us to consider knowledge in our own minds as we function and produce work throughout our days. I asked her if she had any anecdotes from her current college experience. She told me, “A specific example from my life is a lab class I took last semester. We were asked to recall notes from the previous lecture while finding tree samples, as well as recall tree identification. We were also asked to learn information while working on the trail and recall it later in the class period, and follow multi-step labs in a short amount of time.” This class presented multiple challenges to working memory. First, the students had to bring knowledge from the classroom to the field, and then they had to bring knowledge from the field back into the classroom, all without notes. Next, they had to engage in labs that required a specific set of actions to be performed in a certain order. Activities like these are tasks for working memory, which serves what these students will need as they move into the workforce—an ability to relate and retain information in a meaningful way. She reflected on how her Montessori education served her in these skills: “The Montessori experience inherently lends itself to working memory, because there is a process to almost everything we do. I learned how to remember and executive multi-step processes from a very young age.” Throughout all the age levels, beginning at 18 months, the children engage in processes for every activity. There is a beginning, a middle, and an end, with many steps, which all must be completed in a certain order for a student to be successful. Because they have the freedom to engage with the process on their own, practicing and exploring through each step, they absorb the order of a process. And it becomes a natural skill for them to look for the logical steps of any activity, as well as the information needed to do the work to satisfaction, all important elements of working memory. Emotional control: the ability to manage emotions A Montessori graduate in her 20s spoke to me about emotional control: “My foundation for emotional regulation continues to set me apart from my peers who attended traditional schooling. I attribute my organized way of handling difficult situations and my social skills to the freedom that Montessori allowed me.” The ability to manage emotions plays an important role in productivity and success in life. Without equilibrium, we are easily thrown off track from our goals or plans, and can struggle to make positive social connections. She went on to share, “My ability to look at social scenarios objectively and tackle obstacles with composure and logic is directly correlated to how my emotional development was supported early in life.” Emotional regulation can be elusive. While strong feelings are not inherently negative, the inability to manage them is. One of the most powerful indicators of mental stability is the skill of acknowledging emotions without letting them overpower situations. Our graduate reflected on how she thinks she developed this foundation: “I think my ability to emotionally regulate began with Practical Life activities when I was 18 months old. These activities taught me to follow a logical sequence of steps and gave me experiences with concentration from a very young age.” I invited her to elaborate on how her concentration led to emotional skills. “The ability for a young child to maintain this state of deep concentration and stick to a task for extended periods of time lays the foundation for emotional and personal development. These Montessori activities allow each child to reach a state of normalization and, as a result, create self-regulation. When a child is concentrating and in that normalized state they are in complete control of their emotions.” Normalization is a term that Dr. Montessori used to describe the calm, content state that children enter after they have deeply engaged in productive and meaningful work. She observed that, indeed, normalization led to emotional regulation (For more information on normalization, read our blog What is Normalization?) Having the freedom to choose work that is interesting, and the time to deeply concentrate on this work, allows normalization—and emotional regulation—to flourish. Flexibility: the ability to revise plans I met with a mother to talk about her high school daughter’s experience during her freshman year. The concept of flexibility stood out for her as she considered her child: “She did not reveal a great deal of innate flexibility through her childhood.” She credits her Montessori experience with this development. She was not forced into flexibility by a top-down approach. Instead, she and her classmates learned to choose flexibility and how to thrive in an ever-changing world. A student’s day in a Montessori classroom is not tightly scheduled. While there are specific and precise ways to do activities, and there is an overarching expectation that each student will complete necessary work over a period of time, they have a great deal of freedom to make choices and change plans as their social and academic needs evolve throughout the day. They practice and experience flexibility from their own initiative as they assess what they want to do with what needs to be done, and which peers and work materials are available to them. These freedoms increase as the children approach the Secondary Level—their seventh and eighth grade years. At Forest Bluff, the ten-day Secondary Level winter trip traditionally alternates between an outdoor dog-sledding experience and travel to Washington, D.C., to learn about American government and history. In 2021, in the thick of Covid, her class had to cancel their trip to Washington, D.C., at the last minute and pivot to a different outdoor trip. Because students are so heavily involved in the planning of these trips, they were the ones responsible for making the changes in logistics and schedules. They were flexible because they had to be. They practiced their skills in the change of plans, and they viscerally experienced the drawbacks and benefits of changing the trip. “They had an entire trip changed,” her mother shared. “That’s real flexibility.” Her daughter has brought this relationship to flexibility into her high school experience. Now, instead of being overwhelmed or rigid when circumstances change, her mother told me, “She not only can pivot easily, but she sees the benefit of it.” Goal-directed persistence: the ability to stick with an action or activity in pursuit of a goal An 18-year-old shared how her experience in Montessori served her ability to persist through challenges in high school. She told me that she viewed them as learning opportunities. Her perspective bolstered her persistence by giving her purpose and confidence. “One of my first major challenges in high school was the first week of finals freshman year. I was not used to taking tests at all, let alone several per day for a full week.” When I asked her how she had approached this time period, she told me she believed her Montessori experience actually gave her an advantage in the way she thought about finals. “Instead of viewing the week as a stressful hardship, I saw it as an opportunity to solidify all of the knowledge I had gained throughout the semester.” Her mental shift allowed her to persist through the week and complete her exams successfully. “Because Montessori cultivated an environment that fostered perseverance and personal growth through challenges, I viewed each test as an opportunity instead of a hardship.” I asked her how she thought Montessori specifically supported this perspective: “I remember when I was very young, I was struggling to solve an advanced problem I was encountering for the first time on the large bead frame [a math material]. After an hour of not being able to solve the multiplication problem, I became frustrated and impatient. I went and talked to my teacher who encouraged me to view every step of trial and error as part of my journey to success. That motivated me to keep attempting to solve the problem, as I knew that with each attempt I would learn more and become closer to the answer.” This attitude towards trial and error is an integral part of Montessori, as is the understanding that challenges are an inevitable part of growth and education. Persevering does not simply mean plowing through hardship. Instead, as this high school senior demonstrated, goal-directed persistence thrives when a person has tools at their disposal for making challenges meaningful and valuable. Look for Montessori and Executive Functioning Part III, the final article in our Spring Blog Series, which explores the role of metacognition in Montessori.

Executive Functioning: A set of essential life skills Research tells us that executive functioning skills are an important predictor of positive adult outcomes. They are the foundation for a productive and well-functioning life. These skills matter more than social class, measurements of intelligence, or even mistakes made during childhood and adolescence (Moffitt, et al, 2011). Executive functioning refers to the set of mental and emotional skills necessary to plan effectively, initiate and complete tasks, and solve problems. Developing these skills is a crucial part of living in a meaningful and purposeful way. As parents and educators have come to understand how important executive functioning is for a successful adult life, it has become the focus of many conversations and goals for educational practices. Schools have sought to integrate applications into their curriculum, and practitioners offer tutoring and workshops on developing these habits for children and adults. As more research is conducted on the relationship between executive functioning and educational practices, it has become clear that Montessori uniquely supports the development of these important life skills. A systematic review examining academic and non-academic effects of a Montessori education revealed that (along with other positive effects) Montessori has a positive effect on executive functioning (Randolph, et al, 2023). People who have attended a Montessori school have, on average, greater executive functioning than those who have attended only conventional schools. Children in Montessori classrooms have up to three hours of uninterrupted work time; they choose what they will do and how long they will do it; they experience regulating their emotions when they concentrate deeply; and, as they get older, they propose projects to work on, determine the scope of the project, and then have time to follow through with all parts of the task. These, and many other qualities of the Montessori approach, all support development of executive functioning. But what are the skills that make up executive function skills? How do these skills show up in Montessori alumni? And how did their educational experiences support their development? Executive functioning can be described as including: sustained attention, task initiation, organization, time management, planning/prioritization, response inhibition, working memory, emotional control, flexibility, goal-directed persistence, and metacognition (Guare et al, 2013). Montessori Alumni Reflect on their Executive Functioning Sustained Attention: the ability to keep paying attention A sophomore in college shared with me that she knows her abilities with sustained attention come from her experience in Montessori. She said, “I attribute a lot to the freedom Montessori gave me to pursue my interests and manage my time. Instead of school being a mundane task of listening to a lecturer, I associated learning with exploration and autonomy.” These positive associations ensured that her foundational relationship to her education was a positive one, giving her the groundwork for wanting to engage in work and find ways to complete necessary tasks. I asked her to describe what this skill looks like for her today in her college experience. She answered, “Even though work can be bothersome, I have the tools and motivation to focus on one task and manage my time accordingly.” Sometimes parents wonder if their children will retain the ability for sustained attention when they transition to a conventional school, where they aren’t allowed to pursue their interests as heartily. But in her answer to me, our sophomore shares that it has. Even when her work is “bothersome,” she finds her abilities carry through. I asked her where she thought her skills for sustained attention were rooted now. Did it come from sheer discipline? Did it feel innate? “I don’t think my focus is innate,” she shared. “Instead, the habits I’ve committed myself to keep me on track. Organizing my day in a planner has majorly increased my focus, a habit that started in Montessori. I write down everything I need to accomplish and prioritize the most important tasks.” What I found striking about her discussion of sustained attention was my dawning understanding that her ability to concentrate was not a thoughtless ability. She provided a scaffolding for herself with habits and motivation that allow this skill to flourish—habits and motivation that developed in Montessori. In truth, the goal of education is not to grant every child every innate strength. It is to support them as they develop, growing towards abilities with healthy habits and coping mechanisms. “My desire to get my work done has always pulled me back to my work,” she shared, as she reflected on her words. “I find satisfaction in completing tasks efficiently and choosing how to spend the rest of my day.” Task initiation: the ability to get started on work that needs to be done One parent asked her freshman son which elements of executive functioning he acquired through his Montessori experience. “All of them!” he answered earnestly. A gratifying answer, to be sure, but when pressed, he said that the concept of task initiation stood out to him. “It’s not hard for me to start doing my homework or studying for a test. I know that the earlier I start, the sooner I’ll be finished. Homework is hard, but I don’t have trouble getting started.” He elaborated on how he saw this ability originating. “In Montessori, the teacher is not prompting you regularly to do anything. You need to get started on your own. You are the one who has to remember to start doing your work.” When I asked him what he had been experiencing in those moments in the classroom, he shared, “The teacher isn’t sitting around available to us all the time. She is working with someone else or giving them a lesson. Because of that, the students know that their work is their responsibility.” A teacher-centered classroom by its nature revolves around the teacher. Students stop and start their work by their teacher’s instructions. But a Montessori classroom is work-centered. For the most part, the students themselves initiate their activity, giving them repeated practice in task initiation. “It wasn’t easy for me to do this when I was in the Upper Elementary,” he told me. “I had to practice getting started. But now that I’m in high school it’s something that I’m used to and can do easily.” Task initiation plays an important role in high school, college, and beyond. This student went on to tell me more about how he saw this skill serving him in his life: “It’s a really good ability to be able to start something even if you don’t want to. You need to be able to do it to accomplish anything in life.” I asked him when he thought it would be most useful to have this ability, and his response was simple: “Task initiation is useful in almost every situation.” Organization: the ability to coordinate or arrange in a logical order A student currently in high school told me that he attributes his organizational skills to his time in Montessori. “In each of the classes, we had personal drawers where we kept all our work. It was our responsibility to keep that area clean and organized, and students took turns checking each other’s drawers. Having that responsibility gently instilled in me the ability to be organized.” I asked him how he sees that manifesting in high school and he shared, “My work folders are organized. My backpack is organized. My computer tabs are organized. And anytime I notice that something is cluttered, I get rid of the stuff I don’t need. This gives me a reminder of what I need to do.” In this comment, he reveals to me that he not only is organized, but that he intuitively understands the benefits of it. By keeping his work in order, he is able to quickly identify essential tasks, and save himself time spent wading through items that create noise. This, from a fifteen-year-old boy. When I press him on his experience with the drawers, I ask him what else he thinks served his ability to be orderly now. Was it just the physical space of the drawers? He acknowledges that the personal responsibility instilled in projects from start to finish would have also played a role. “In high school, the teachers tell us what to do all the time. We don’t have to make many decisions or even plans. In Montessori, we were responsible for so many more parts of our work: what we were going to do, how to get started, how much to cover, when to finish. I think that we practiced organization all day every day in almost everything we did.” In his comment, this young man expresses the beauty of Montessori. It did not do anything to him or even give him anything. Because of the freedom and responsibility it provided, he developed the skill of organization himself. Time management: the ability to use one’s time effectively A young woman shared her experience with time management in high school through an anecdote that occurred at the beginning of her freshman year, in the thick of the pandemic. “I started high school when Covid really hit. One of the skills I used was being able to independently learn. We spent so much of the year on-line learning, and not in person.” This academic arrangement made it even more important for high school students to be able to manage their work and time throughout the day—ensuring they were both effective and efficient with their assignments and projects. “Many of my friends did not do well for two whole years. That’s a long time,” she shared. “I was able to thrive because Montessori taught me how to independently learn, and stay on task.” Her independent learning meant that she was making decisions about structuring her time throughout the day, and then making sure that she completed her assignment on her own. When I asked her how she was able to manage her time so well at such a young age, she said, “I did not need someone constantly looking over my shoulder. That was a skill that I got from Montessori.” Because the day in a Montessori classroom is not strictly structured, the students have freedom—and the expectation—to manage their time throughout the day. As they get older, they have more and more responsibility for their work, with regular check-ins with their teacher to make sure they are making progress. They develop time management skills as they practice regular independence and accountability. Planning/prioritization: the ability to think ahead about what needs to be done and in what order For this trait, I had the opportunity to speak to a mother who attended Montessori school herself and who has two children who graduated from Montessori. This skill was intriguing for her because one of her children has deep inherent skills with the planning and prioritization element of executive functioning, while she and her daughter have inborn challenges in this area. “My son, who is extremely good with his executive functioning skills, sees life from a hill. He sees everything he has to do for the next three weeks. He can prioritize and plan easily. His challenge is to not feel overwhelmed by his tasks, because he is able to see them all, but he uses his (multiple!) planners to manage what he needs to do and when.” She went on, “On the other hand, my daughter and I only see one thing in front of us at a time. The other things are an invisible blur. We know it’s there, but it’s not present in our minds.” This can make it hard to plan, and even harder to prioritize. I asked how Montessori has served them in their years after graduation—her successful career and her daughter’s successful first two years of high school. Clearly, their inherent challenges have not prohibited them from productivity and achievement. “The benefit of Montessori was that we learned a lot of coping mechanisms and strategies. Starting in the Elementary, students are recording in their work journal what they are doing, as well as how much time it’s actually taking them to do something. They aren’t predicting how much time it will take yet, but they have to repeatedly reflect on how much time they spent on it and what they got done.” She went on: “In conventional school, time is managed for you. You are in lockstep with your class. You don’t get to work at your own pace. You don’t even know what your pace is. In Montessori, the students are asked to reflect on their time in a serious way. By the time they are in Secondary Level, they are thinking ahead about how much work they have and how long it is going to take.” Montessori students are well-versed in planning and prioritization by the time they are completing high school, and use those skills effectively for managing their work. This alumni mother reflected on how apparent this is in an older high school student: “I remember speaking to a high school teacher about a Montessori graduate who was in his class. He said, ‘It’s like he has a sixth sense of how to get work done.’” Look for Montessori and Executive Functioning Part 2 , the next article in our Spring Blog Series. Alumni share how Montessori helped them to develop important life skills such as flexibility, emotional control, and response inhibition.

I love finding ways that Montessori’s educational approach inherently addresses human needs. When I look at books espousing the best ways to teach, the best ways to conduct business, or the best ways to be healthy, I usually find that the Montessori approach already incorporates the recommended practices—and always in an integrated, natural way. The Forest Bluff Directors and I are witnessing this once again while reading our latest teacher group discussion book at Forest Bluff, The Innovator’s DNA: Mastering The Five Skills of Disruptive Innovators, by Jeff Dyer, Hal Gregersen, Clayton M. Christensen. In today’s world, the ability to innovate is key to solving problems large and small. I would argue that it has always been important for human survival and progress, but it has become a more urgent need, and now it’s a buzzword for educators. The aforementioned authors explain that to create something new—to innovate—a person needs to associate (connect ideas), network with others (socialize), observe (reflect), question (lead with your curiosity), and experiment (be unafraid to try things and fail). In the Montessori approach, you can see how these practices, or habits, are all actively encouraged and cultivated. Each of these important aspects of innovating are worked into the educational approach seamlessly. Dr. Montessori was simply following what made sense for optimal human development. For one example, Montessori education has captured an essential key to children’s learning: presenting the world in context, from the whole to the parts, with a deliberate, ongoing opportunity for children to associate topics, themes, and details of information. Associating is a crucial skill. Montessori’s approach creates habits in children’s thinking that prepare them for a life of innovative creativity and problem solving by constantly encouraging them to associate.